Edition 49: Friends of Warminster Maltings

Bonfire Night!

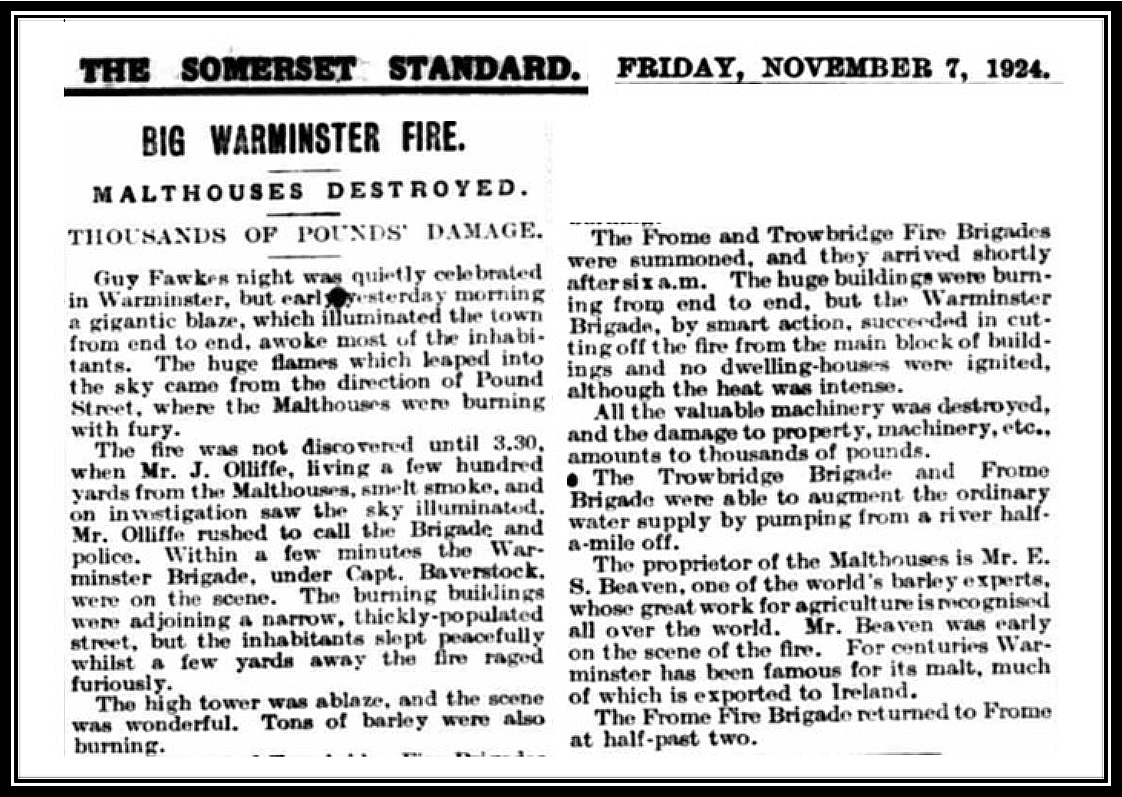

On this day, 99 years ago, Warminster Maltings suffered a rather disastrous and costly event!

There was a fire which, amongst much other damage, destroyed the ‘pyramid’ style roofs on kilns 3 and 4.

Warminster residents will know this is something we have been working on reinstating – the final phase of our 20+ year restoration project – and there will be more exciting news on this imminently.

But, back to the anniversary of this catastrophic event. It was actually a fairly typical problem suffered by many ‘floor maltings’ at the time. The combination of hot coals, partial timber structures and dry barley and malt grains was always a recipe for disaster.

The ‘Somerset Standard’ reported that “The high tower [the sweater kiln at the other end of the building] was ablaze, and the scene was wonderful”.

I don’t believe that the then custodian, Dr. Beaven, would have agreed it was “wonderful”, but he was fortunately unfazed, and immediately set about rebuilding his malthouses.

And so here we are, 99 years later, still going strong!

“What Goes Round…”

‘Floor malting’ is a centuries old process. There is a Saxon site under excavation close to the Wash in north-west Norfolk, where they have discovered a whole complex of what appear to be malthouses – the archaeologists visited us to establish that the Saxon remains have the same “footprint” as Warminster Maltings. Less than 200 years ago there would have been a small malthouse in every third countryside parish you travelled through.

But at the beginning of the 20th century, new technology from the Continent crept into the U.K. malting industry. It was described as ‘pneumatic malting’, a fully mechanised, controlled environment process which allowed for both greater volume and less time required for each batch of malt, by effectively forcing the modification of the barley into the malt. This new technology was capable of reducing the price of malt significantly but was initially judged by the brewing industry to produce an inferior product and was soundly rejected!

In the aftermath of World War 2, however, the drive towards the industrialisation of our food and drinks industries moved up a gear, which meant Britain’s largest breweries became far more receptive to the price of malt, than to the superior quality of ‘floor made’! So, by the early 1960’s, large scale ‘pneumatic maltings’ priced much of the ‘floor maltings’ industry out of business. By the end of the 1970’s only a handful of ‘floor maltings’ still remained operational, including Warminster Maltings of course.

Today, craft brewers and distillers are returning to being more discerning about the quality of their malt than just focused on the price, and in doing so, they are returning to recognising ‘floor made’ malt as being a superior product, which, in turn, can markedly enhance their own.

Up in Scotland, there is a small number of iconic distilleries which still operate their own ‘floor maltings’, and there is a brand new small distillery that has just opened on Speyside, Dunphail, which includes its own ‘floor maltings’ modelled on Warminster. Of the former, three of these are owned by the Japanese based Suntory conglomerate, one of the world’s largest producers and distributors of spirit drinks. It seems that Suntory agrees with the view that ‘floor made’ malt is a superior product, to the extent that they are now building two brand new ‘floor maltings’, one each at their Hakusha and Yamasaki distilleries in Japan.

From my point of view, this is an extraordinary turn of events. Ever since 2001, when I undertook the task of keeping Warminster Maltings going, I was much derided for trying to prolong a “sunset” industry and have constantly been challenged over the extra cost of ‘floor made’ malt. Now, it seems, both brewers, and distillers, want to return to the very natural process that engineering and scientific intervention have tried, but struggled, to truly replicate.

It seems the old saying rings true, “What goes round, comes round”!

The Barley Tree

Different barley varieties have existed forever. Originally, many were named after the place in which they were discovered, often spotted as a small group of plants growing in the wild. These selections became known as “landrace” varieties, propagated by the farmers who found them. But these varieties were unstable in as much as they would not easily travel. They belonged where they were found, and when a particular variety was found to be especially good, it took very many years for farmers to adapt them to the climate and topography of a different region.

Then along came our very own Dr. Beaven, at Warminster, who practiced barley breeding, by crossing many different “landrace” varieties, until, in 1905, he created the very first “genetically true” variety of barley in the world, our famous Plumage Archer. This barley was stable, and so it would travel. From then on barley breeders worldwide took over the selection of new varieties, and the rest is history, as they say.

Except, “the rest” has become a quest driven more by the agronomic virtues of each new variety, than the quality traits demanded by consumption. In the process, the flavour of individual barley varieties seems to have been sacrificed on the altar of economic performance. So, we are now attaching a level of importance to a secondary group of barley varieties which follow directly from the original “landrace” varieties, which we are now labelling “heritage varieties”. These are the varieties that followed on from Dr. Beaven’s work and were bred in the first half of the 20th century. What is important about them is they retained distinctive flavours because their conception was guided by barley breeders more focused on consumption than production.

So, because you could say it was us at Warminster who started all this, and, courtesy of Maris Otter, have since sought to perpetuate matters (Robin Appel Ltd owns the Production and Marketing Rights to Maris Otter), we have produced a ‘Barley Tree’, entitled “The Evolution of U.K. Heritage Barleys”. We have yet to produce it as a Poster, but we can if demand exists.

Demand for the actual barleys, on the other hand, is very real indeed, with an extraordinary level of interest from the distilling sector in particular. You could say another example of “what goes round, comes round”!

Robin Appel